Breeding adult

This plumage is acquired in late winter or early spring (February-early May) and is held into the late summer or early fall (August-October), and virtually all individuals observed in spring in B.C. will be in this plumage. The upperparts (back, scapulars) are brownish-black with whitish speckling or mottling and a few rusty-buff markings. The ypperwing coverts and flight feathers are relatively uniformly greyish-brown, usually with slightly paler feather edges on most feathers. The rump and uppertail coverts are white with some blackish spots. The short, squared tail is greyish. The underparts (breast, belly, sides, flanks, undertail coverts)are whitish with heavy, dense blackish-brown barring throughout. The underwing coverts are largely whitish, contrasting with the mostly dark underparts and grey flight feathers. The neck and nape are whitish with dense, fine blackish-brown streaking and mottling, including on the chin, throat, and malar area. The lores and ear coverts are rufous and the crown is rufous with fine blackish streaking; the supercilium is whitish and mostly unmarked. The iris is dark, the long, slender, slightly drooping bill is blackish, and the legs and feet are greenish-yellow.

Non-breeding adult

This plumage is acquired in late summer or early fall (August-October) and retained into the following late winter or early spring (February-early May); very few individuals, except occasional adults during the latter part of fall migration, are observed in this plumage in B.C. Birds in non-breeding plumage have uniformly pale greyish upperparts (back, scapulars, upperwing coverts) that contrast with the mostly clean white rump and uppertail coverts and the darker grey flight feathers and primary coverts. The tail is greyish, as in breeding plumage. The underparts are primarily whitish with some faint greyish speckling on the breast and sides, rarely extending into short, faint streaks on the flanks. The underwing coverts are whitish. The head and neck are pale greyish, with faint, fine, slightly darker grey streaking or speckling on the sides of the face and neck, a darker brownish-grey crown, darker grey lores, and a whitish supercilium. Bare part colouration is similar to breeding-plumaged birds.

Juvenile

Birds retain this plumage into fall (September) of their first year, and the vast majority of individuals encountered in B.C. are in this plumage. The upperparts (back, scapulars) are primarily dark blackish-brown with pale feather edges; the scapulars are variably edged with rufous. The feathers of the upperwing coverts and tertials are brownish and are finely edged with pale buffy-white, giving the entire upperparts a distinctly scaly appearance. As with the adults, the rump and uppertail coverts are whitish and the tail is grey. The underparts are primarily whitish with a variable buffy wash on the breast and sides and often some fine grey or buffy-grey streaks on the sides and flanks. The head and neck are greyish-white with a variable buffy wash, with fine grey streaks on the sides of the face and neck, a whitish chin and throat, a whitish supercilium, darker brownish-grey ear coverts, and a darker and browner, finely dark-streaked crown. Bare part colouration is similar to that of the adults.

Measurements

Total Length: 21-22 cm

Mass: 48-68 g

Source: Klima and Jehl, Jr. (1998); Sibley (2000)

Calidris himantopus (Bonaparte, 1826)

Stilt Sandpiper

Family: Scolopacidae

Species account author: Jamie Fenneman

Stilt Sandpiper

Family: Scolopacidae

Species account author: Jamie Fenneman

Species Information

Biology

|

Habitat

|

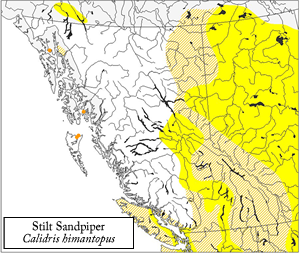

Distribution

|

Conservation

|

Taxonomy

|

Status Information

|

BC Ministry of Environment: BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer--the authoritative source for conservation information in British Columbia. |